The Bayeux Tapestry

Posted by Jeff Ezzell on

Introduction

The Bayeux Tapestry (French: Tapisserie de Bayeux) is a 50 cm by 70 m (20 in by 230 ft) long embroidered cloth, done in painstaking detail, which depicts the events leading up to the 1066 Norman invasion of England as well as the events of the invasion itself. Once thought to have been created by William the Conqueror’s wife Matilda of Flanders it is now believed to have been commissioned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William’s half brother.

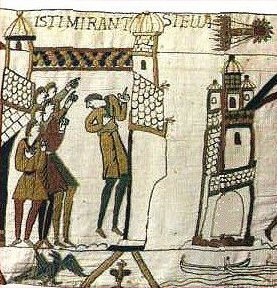

The Tapestry is valued both as a work of art and as a source concerning the history of the Norman Conquest. Decorative borders on the top and bottom show medieval fables and the Tapestry also provides historical data concerning military equipment and tactics during the era around 1100. It also includes images of Halley’s Comet. Originally intended to legitimize the Norman power in England, the tapestry is annotated in Latin.

Nearly hidden in the Bayeux Cathedral until its rediscovery in the seventeenth century, it was moved several times to protect it from invaders. It is presently exhibited in a special museum in Bayeux, Normandy, France, with a Victorian replica in Reading, Berkshire, England.

Construction and Technique

In common with other embroidered hangings of the early medieval period, the Bayeux Tapestry is not a true tapestry in which the design is woven into the cloth, but is in fact an embroidery.

The 70 scenes of the work are embroidered in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground using two methods of stitching: outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures. The linen is assembled in panels and has been patched in numerous places.

The main yarn colors are terracotta or russet, blue-green, dull gold, olive green, and blue, with small amounts of dark blue or black and sage green. Later repairs are worked in light yellow, orange, and light greens. Laid yarns are couched in place with yarn of the same or contrasting color.

Contents

Overview

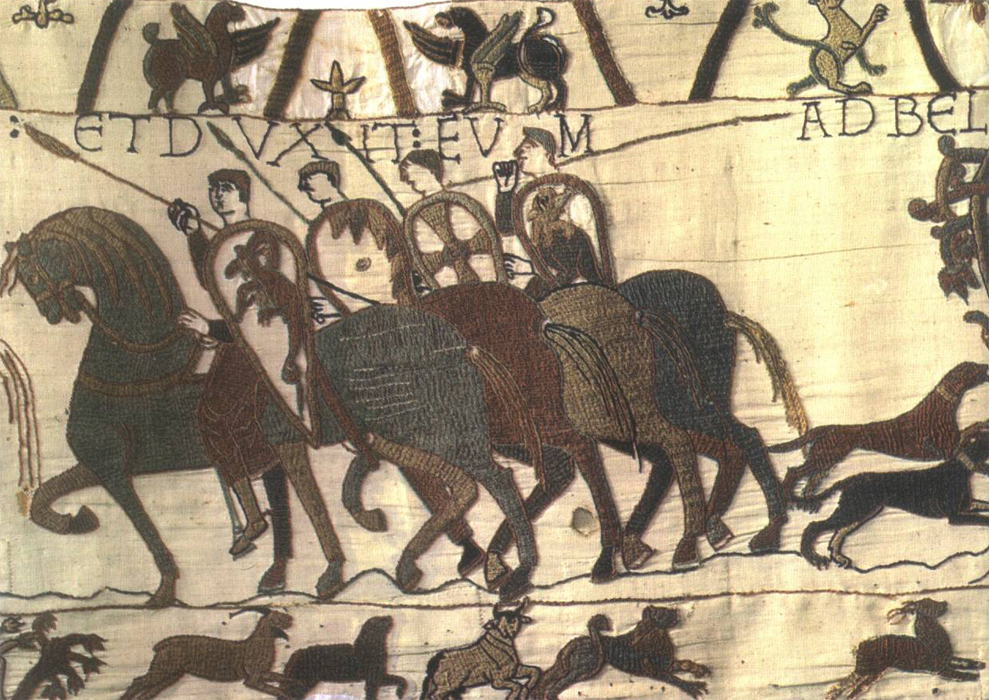

The Tapestry tells the story of the Norman conquest of England. The two combatants are the Anglo-Saxon English, led by Harold Godwinson, recently crowned as King of England, and the Normans, led by William the Conqueror. The two sides can be distinguished on the Tapestry by the customs of the day. The Normans shaved the back of their heads, while the Anglo-Saxons had mustaches.

The Tapestry begins with a panel of King Edward the Confessor, who had no son and heir. Edward appears to send Harold Godwinson, the most powerful earl in England to Normandy. When he arrives in Normandy, Harold is taken prisoner by Guy, Count of Ponthieu. William sends two messengers to demand his release, and Count Guy of Ponthieu quickly releases him to William. William, perhaps to impress Harold, invites him to come on a campaign against Conan II, Duke of Brittany. On the way, just outside the monastery of Mont St. Michel, two soldiers become mired in quicksand, and Harold saves the two Norman soldiers. William’s army chases Conan from Dol de Bretagne to Rennes, and he finally surrenders at Dinan. William gives Harold arms and armor (possibly knighting him) and Harold takes an oath on saintly relics.

It has been suggested, on the basis of the evidence of Norman chroniclers, is that this oath was a pledge to support William’s claim to the English throne, but the Tapestry itself offers no evidence of this. Harold leaves for home and meets again with the old king Edward, who appears to be remonstrating Harold. Edward’s attitude here is reprimanding toward Harold, and it has been suggested that he is admonishing Harold for making an oath to William. Edward dies, and Harold is crowned king. It is notable that the ceremony is performed by Stigand, whose position as Archbishop of Canterbury was controversial. The Norman sources all name Stigand as the man who crowned Harold, in order to discredit Harold; the English sources suggest that he was in fact crowned by Aldred[1], making Harold’s position as legitimate king far more secure.

A star with streaming hair then appears: Halley’s Comet. The first appearance of the comet would have been April 24, nearly four months after Harold’s coronation. The news of Harold’s coronation is taken to Normandy, where William then builds a fleet of ships. The invaders reach England, and land unopposed. William orders his men to find food and a meal is cooked. A house is burnt, which may indicate some ravaging of the local countryside on the part of the invaders. News is brought to William, possibly about Harold’s victory in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, although the Tapestry does not specify this.

The Normans build a mote and bailey (wall) to defend their position. Messengers are sent between the two armies, and William makes a speech to prepare his army for battle.

At the Battle of Hastings, fought on October 14, 1066, the English fight on foot behind a shield wall, while the Normans are on horses. The first to fall are named Leofwine Godwinson and Gyrth Godwinson, Harold’s brothers. Bishop Odo also appears in battle. The section depicting the death of Harold can be interpreted in different ways, as the name “Harold” appears above a lengthy death scene, making it difficult to identify which character is Harold. It is traditionally believed that Harold is the figure with the arrow in his eye. However, he could also be the figure just before with a spear through his chest, the character just after with his legs hacked off, or could indeed have suffered all three fates or none of them. The English then flee the field. At the time of the Norman conquest of England, modern heraldry had not yet been developed. The knights in the Bayeux Tapestry carry shields, but there appears to have been no system of hereditary coats of arms.

The Tapestry has 626 human figures, 190 horses, 35 dogs, 506 other birds and animals, 33 buildings, 37 ships, and 37 trees or groups of trees, with 57 Latin inscriptions. It shows three kings: Edward the Confessor (1042-1066); Harold II (January-October 1066); and William of Normandy (1066-1087). Two clerics are also shown: Bishop Odo of Bayeux, and Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury. Only three women are depicted in the Tapestry: Edward the Confessor’s wife Edith, a woman apparently fleeing from a burning building, and a woman named Aelfgyva (see Modern history of the Tapestry).

Mysteries of the Tapestry

The Tapestry contains several mysteries:

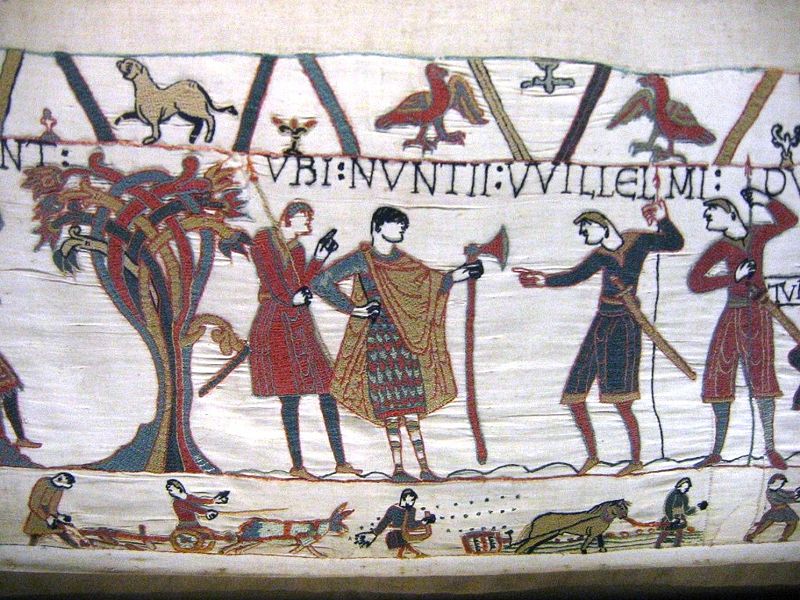

- There is a panel with what appears to be a clergyman touching or possibly striking a woman’s face. The meaning of the inscription above this scene is obscure (ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva, “where [we see] a certain cleric and Ælfgifu,” see image in the Modern History section below). There are two naked male figures in the border below this figure; the one directly below the figure is squatting and displaying prominent genitalia, a scene that was frequently censored in former reproductions. Historians speculate that it may represent a well-known scandal of the day that needed no explanation.

- At least two panels of the Tapestry are missing, perhaps even another 6.4 m (7 yards) worth. This missing area would probably include William’s coronation.

- The identity of Harold II of England in the vignette depicting his death is disputed. Some recent historians disagree with the traditional view that Harold II is the figure struck in the eye with an arrow even though the words Harold Rex (King Harold) appear right above the figure’s head. However, the arrow may have been a later addition following a period of repair as evidence of this can be found in engravings of the Tapestry in 1729 by Bernard de Montfaucon, in which the arrow is absent. A figure is slain with a sword in the subsequent plate and the phrase above the figure refers to Harold’s death (Interfectus est, “he is slain”). This would appear to be more consistent with the labeling used elsewhere in the work. However, needle holes in the linen suggest that, at one time, this second figure was also shown to have had an arrow in his eye. It was common medieval iconography that a perjurer was to die with a weapon through the eye. So, the Tapestry might be said to emphasize William’s rightful claim to the throne by depicting Harold as an oath breaker. Whether he actually died in this way remains a mystery.

- Above and below the illustrated story are marginal notes with many symbols and pictures of uncertain significance.

Origins

The earliest known written reference to the Tapestry is a 1476 inventory of Bayeux Cathedral, which refers to “a very long and narrow hanging on which are embroidered figures and inscriptions comprising a representation of the conquest of England”.[2]

French legend maintained the Tapestry was commissioned and created by Queen Matilda, William the Conqueror’s wife. Indeed, in France it is occasionally known as “La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde” (Tapestry of Queen Matilda). However, scholarly analysis in the twentieth century has concluded that it probably was commissioned by William’s half brother, Bishop Odo.[3] This conclusion is based on three facts: 1) three of the bishop’s followers mentioned in the Domesday Book appear on the Tapestry; 2) the Bayeux Cathedral, in which the Tapestry was discovered, was built by Odo; and 3) it seems to have been commissioned at the same time as the cathedral’s construction in the 1070s, possibly completed by 1077 in time for display at the cathedral’s dedication.

Assuming Odo commissioned the Tapestry, it was probably designed and constructed in England by Anglo-Saxon artists given that Odo’s main power base was in Kent, the Latin text contains hints of Anglo Saxon. Other embroideries originate from England at this time and the vegetable dyes can be found in cloth traditionally woven there.[4] Assuming this was the case, the actual physical work of stitching was most likely undertaken by skilled seamstresses. Anglo-Saxon needlework, or Opus Anglicanum was famous across Europe.

Reliability

While political propaganda or personal emphasis may have somewhat distorted the historical accuracy of the story, the Bayeux Tapestry presents a unique visual document of medieval arms, apparel, and other objects unlike any other artifact surviving from this period. Nevertheless, it has been noted that the warriors are depicted fighting with bare hands, while other sources indicate the general use of gloves in battle and hunt.

If the Tapestry was indeed made under Odo’s command, he may have changed the story to his benefit. He was William’s loyal half brother and may have tried to make William look good, in comparison to Harold. Thus, the Tapestry shows Harold enthroned with Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, beside him, as though he has been crowned by him. Harold was actually crowned by Aldred of York, more than likely because Stigand, who received his place by self-promotion, was considered corrupt. The Tapestry tries to show a connection between Harold and the bishop, making his claim to the throne even weaker.

Modern History of the Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry was rediscovered in the late seventeenth century in Bayeux (where it had been traditionally displayed once a year at the Feast of the Relics) (November 5), and engravings of it were published in the 1730s by Bernard de Montfaucon. Later, some people from Bayeux who were fighting for the Republic wanted to use it as a cloth to cover an ammunition wagon, but luckily a lawyer who understood its importance saved it and replaced it with another cloth. In 1803, Napoleon seized it and transported it to Paris. Napoleon wanted to use the Tapestry as inspiration for his planned attack on England. When this plan was canceled, the Tapestry was returned to Bayeux. The townspeople wound the Tapestry up and stored it like a scroll.

After being seized by the Nazi Ahnenerbe, the Tapestry spent much of World War II in the basement of the Louvre. It is now protected on display in a museum in a dark room with special lighting behind sealed glass in order to minimize damage from light and air. In June 2007, the Tapestry was listed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.

There are a number of replicas of the Bayeaux Tapestry in existence. A full-size replica of the Bayeux Tapestry was finished in 1886 and is exhibited in the Museum of Reading in Reading, Berkshire, England.[5] Victorian morality required that a naked figure in the original Tapestry (in the border below the Ælfgyva figure) be depicted wearing a brief garment covering his genitals. Starting in 2000, the Bayeux Group, part of the Viking Group Lindholm Høje, has been making an accurate replica of the Bayeux Tapestry in Denmark, using the original sewing technique, and natural plant-dyed yarn.

Appendix

Notes

- Aldred, died September 11, 1069, an English ecclesiastic, who was Archbishop of York and served Edward the Confessor, the king of England, as a diplomat and as a military leader.

- Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- George Beech, 1995.

- David M. Wilson, 1985, 201-227; and Elizabeth Coatsworth, “Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery,” in Netherton Owen-Crocker, ed., Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1, (2005), 1-27.

- It was the idea of Elizabeth Wardle to make the replica Bayeux Tapestry, now on display in the Museum of Reading. She was a skilled embroiderer and a member of the Leek Embroidery Society in Staffordshire. She researched the Bayeux Tapestry by visiting Bayeux in 1885. The aim of the project was to make a full-sized and accurate replica of the Bayeux Tapestry “so that England should have a copy of its own.” Thirty five women worked for just over a year to create the replica. Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry

References

- Beech, George. Was the Bayeux Tapestry Made in France?: The Case for St. Florent of Saumur (The New Middle Ages), New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995.

- Bridgeford, Andrew. 1066: The Hidden History in the Bayeux Tapestry, Walker & Company, 2005.

- Grape, Wolfgang. The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph, Thames & Hudson, 2004.

- Hicks, Carola. The Bayeux Tapestry: the life story of a masterpiece, London: Chatto & Windus, 2006.

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Boydell Press. Volume 1, 2005; Volume 2, 2006

- Rud, Mogens. The Bayeux Tapestry and the Battle of Hastings 1066, Christian Eilers Publishers, Copenhagen, 2004.

- Wilson, David M.: The Bayeux Tapestry, Thames and Hudson, 1985.

- _______________, ed. The Bayeux Tapestry: the Complete Tapestry in Color, Rev. ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004.